Binary thinking

In which we explore the ambiguity in categorical thinking

Privacy is a tricky thing. It’s rarely absolute – the only way to be completely private is to not exist, and given the level of detail people have come up with about Bigfoot even that’s likely not going to work either. But it’s in the nature of information that knowing one or two pieces allows people to start inferring other information, or at least know better how to find more. If the only thing you knew about me was that I am a research student in psychology, you probably wouldn’t try to identify me by pulling up membership lists of woodworking clubs, for example. I might be there, but it’s not really the most efficient way of finding me.

So we exist in this weird grey space where some information is inevitably going to be known against our explicit desire, but we want to control said information. This is exacerbated by the sheer amount of surveillance – often invisible if not outright hidden – that exists purely to harvest as much information about us as possible, no matter how trivial, and sometimes that information ends up in the hands of people who will use it in ways that harm us – criminals, hate groups, political bodies, among others. In addition, surveillance is sometimes just downright creepy – it may or may not actually harm me if Facebook knows about my foot fetish, but it just makes me really, really uncomfortable that they’re so dedicated to knowing so much about me that they’re willing to violate medical confidentiality or steal information about victims of crimes, or construct detailed profiles on people who don’t even use their site. It’s not hard to point to actual harms that result from this, but even if you can’t it still makes people really uncomfortable.

And to a point this is inevitable. Nothing is hackable, security doesn’t exist. It’s all just matters of degree and chances.

“Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. … Serious harm, I am afraid, has been wrought to our generation by fostering the idea that they would live secure in a permanent order of things. It has tended to weaken imagination and self-equipment and unfit them for independent steering of their destinies. Now they are staggered by apocalyptic events and wrecked illusions. They have expected stability and find none within themselves or their universe. Before it is too late they must learn and teach others that only by brave acceptance of change and all-time crisis-ethics can they rise to the height of superlative responsibility.”

Helen Keller, The Open Door, p. 17-18

For a lot of people, that’s not a problem. Accepting that we are never certain, or that safety is relative, is just a part of being an adult. But some people tolerate this ambiguity and uncertainty worse than others.

You’ve probably heard the term “black and white thinking” or “all-or-nothing thinking” before. If you haven’t, I guarantee you’ve come across examples of it; “you’re with us or against us”, “you either win or lose”, “it’s heck yes or heck no”. The psychoanalytic term is “splitting”, and refers to a ego defence where people are divided into one of two categories – they’re either all good, perfect angels who do no wrong, or they’re completely malevolent devils who exist purely to cause harm out of no motivation other than sheer evil. This is thought to happen when we cannot reconcile the parts of a person we like with the fact that they also have parts that we hate – a particular politician might support privacy, but also be a massive racist. I like that they’re pushing for more legislative respect for privacy, but I’m made very uncomfortable by them doing it so they and their friends can organise to commit hate crimes. So I “split” them in my mind – there’s the privacy politician, and the hate-crime committer, and I treat them as two separate people. One I like, the other I hate. One is good and noble and helping society against a malignant force, the other is hateful and disgusting and stomping down on people because of their ancestry.

Personally, I find psychoanalysis, at best, vaguely interesting in its suggestions, but more often totally bonkers and often unfalsifiable1. That said, there are a lot of very smart people who like it, so take that for what it’s worth.

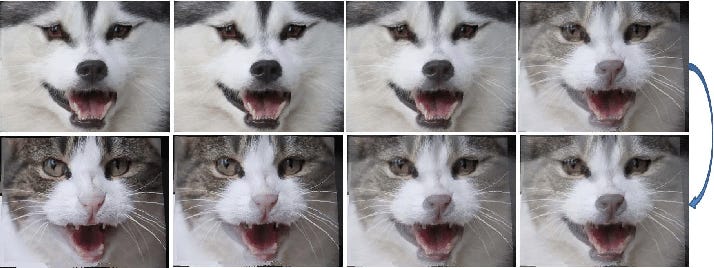

This black-and-white thinking or “splitting” is a specific case of what’s more generally known as “dichotomous thinking” or sometimes “categorical thinking”, where people only think about topics in rigid, opposed categories, with little to no admission of ambiguity. This is best illustrated with an example:

The above image depicts an image of a dog slowly changing into a picture of a cat. We’d all agree that the picture on the top left is definitely a dog, and the bottom left is definitely a cat, but how do we interpret the images in the middle? Is the top-right a cat or a dog? What about the bottom-right? The point is how willing are we to treat a given image as kind-of cat, kind-of dog? We can have three categories, “dog”, “cat” and hybrid, but that’s just dodging the question. To what extent to we force ambiguous stimuli into certain categories? 2

Now, it’s tempting to say “well, that’s obviously bad and wrong. We should treat ‘dog/cat’ or ‘friend/enemy’ not as categories, but as a gradient with a lot of points in between”. But ironically, it’s never that simple. We need categories to function, because a lot of behaviour is categorical. Even if we accept that there is a wide variance between “threatening” and “non-threatening”, a police officer has to either shoot or not-shoot, there is no middle ground there. A person facing criminal charges is found “guilty” or “not-guilty”, there is no such thing as “35% guilty”. I either have enough money to catch the bus or I don’t. I either have the ingredients for a given dish or I don’t. Either I make my deadlines or I don’t. Either I get this medical treatment or I don’t. Either information leaks, or it doesn’t.

Ironically, this is something that people vary in in a more-or-less continuous way. There’s even a scale developed that clearly shows this, but I think you’ll find even your anecdotal experience shows this. I have a few friends who very much do not like ambiguity, they will basically force any situation into one of a number of categories, while I have another friend who basically revels in ambiguity and avoids putting anything into categories unless they absolutely must. Most people vary – some like categories very much in one circumstance but aren’t overly fussed in another, or are generally pretty loose or tight but might move depending on their mood. I know I get really categorical when I’m grumpy.

This tendency towards dichotomous thinking is obviously closely related to “intolerance of ambiguity” or “intolerance of uncertainty”. There’s some minor differences, but for our purposes we can define both of these as a tendency to react to ambiguous circumstances with feelings of discomfort and to view it as in some sense hostile or threatening. The paper above has a really good part I’ll just quote (taken from pages 595 and 596):

Firstly, the term ‘‘intolerance’’ has been used and defined as an individual tendency to perceive or interpret a situation (environment) as a threat or a source of discomfort, anxiety and disagreement in studies involving ambiguity...Secondly, in both cases, individuals respond to this perceived threatening situation with a set of cognitive, emotional and behavioural reactions.

So if you, for whatever reason, do not like ambiguity, you’re going to react in certain ways, and one of those might be to force the situation into certain categories. If I don’t know if my ISP is tracking my Internet usage (and I care), I’m probably going to assume that either they are or they aren’t, rather than sit in that uncertainty and ambiguity.

What does this have to do with privacy?

So my intention was to point out bad practices in the privacy “community” which is pretty blatant examples of this – if you’re not totally private, you’re totally public. Something is either secure or insecure. If you’re not doing everything you’re effectively doing nothing. But I’m not going to do that. Partially because I don’t think it’s helpful, and partially because it’s boring.

So instead I’m going to talk about how this is something we all need to think about. The thing about the mass surveillance is that it is, for the most part, invisible, we don’t know if we’re being watched in this moment. I don’t know whether my VPN provider is trustworthy or not – I think they are, but at the end of the day I’m having to trust the research I’ve done and what other people have told me. And security is never absolute – the only system that is unhackable is one that has no way of communicating with the outside, is encased in concrete, and has been shot into the sun. We all have to deal with ambiguity to at least some extent.

Now, as I said before, it’s tempting to just say “well, we need to be better about dealing with that ambiguity”. And to a point, sure. But at the end of the day, we need to take certain categorical choices. Do I use a password manager or not ? (Yes. Yes, you should.) Which one do I use – Bitwarden, KeePass, 1Password, LastPass, ProtonPass? 3 You can, theoretically, kind of use a password manager, but I’m pretty sure that’s fairly pointless. Do I use a VPN or not? If so, which one? Ambiguity is not necessarily a good thing – ambiguous communication can be disastrous, for example. And if you’re prone to anxiety, ambiguity can be a real problem! It can be really comforting to be able to see if the oven is on or not – this is part of what drives OCD, after all. People have intrusive thoughts that cause distress, so they develop rituals in order to alleviate that distress. If the thoughts are about disease, then you wash your hands. If you keep thinking you forgot to lock your car, you can go back and check. Even among non-anxiety disorder contexts, confirmation of ambiguous situations can be really helpful – programmers often code in outputs for each stage, so you can see where the program got up to and that it’s still running. When you’re cooking it can be helpful to cut e.g. a meatball open to see if it’s cooked yet or not. If I’m not sure if there’s been a power outage or not, being able to turn on a light and check is very useful.

In fact, I’d go so far as to say that dichotomous thinking is helpful in privacy, if used correctly. Forget the terms “private” and “secure” for a moment. What am I trying to accomplish? Let’s say I do not want my e-mail accounts to be hacked/stolen. I put that in a “do not want” category – being ambiguous about it doesn’t help. Labelling it as “bad” and moving on with the process is much more productive. But maybe I’m less concerned about, say, the account I use to play silly games online – I put that in the “don’t care” pile. Do this a few times, and now I have a list of “things I care about” and “things I don’t” (you can have three if you like, but 2 works for the example). Now, I know what I need to focus my attention on. I’m not going to exert the same effort in the silly-games account as I am my important e-mail account. All of a sudden, I’m able to be a lot more efficient and effective.

This process generalises pretty well. Am I worried about spam phone calls? How about targeted advertising? What about non-targeted advertising? Do I care if Netflix knows what I watch on Netflix? How about my bank knowing where I do my grocery shopping? Maybe I do, maybe I don’t! But by being nicely categorical about things, I’m able to be much more efficient about what I focus on. If I decide that, for example, I’m not fussed about non-targeted advertising, I don’t need to worry about whatever a pi-hole is, and can focus on how I can use cash more.

Black and white thinking can obviously be bad and toxic. It’s notoriously associated with borderline personality disorder, but also narcissistic personality disorder. It’s associated with what this paper calls “undervaluing others”, which is just a fancy way of saying “assuming other people don’t know what they’re doing/talking about”, and perfectionism, and all sorts of other not-fun-times. I haven’t seen anything talking about this, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was associated with various kinds of bigotry or general nastiness to people based on whatever categories the person feels like being unpleasant on. But as with most psychological ideas, I really think just being aware of them – and more importantly mindfully applying them – it can be a really helpful tool.

[Catdog photo taken from here]

Co-incidentally, this is also my view of evolutionary psychology. It can be a really interesting source of hypotheses and ideas to be tested in other perspectives, but as a view in itself I have very little patience for it, especially when it tries to get causative.

Obvious political parallels are obvious. I shall not touch them, and I’d appreciate it if you don’t start arguments in the comments.

I could use all of them, and there’s some value to that, but there’s also quite substantial downsides (which to my mind undercuts the entire point, that being convenience and security).